It was released in the midst of a growing awareness of the shockingly high rates of abduction and murder among indigenous women in the U.S. today — an issue that several members of the cast of Killers of the Flower Moon are all too acquainted with. To honor its 10 Oscar nominations and shine on a light on the indigenous talent involved, Apple and the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian hosted a special event in Washington, DC. The Watercooler’s Felipe Patterson attended and interviewed two of the film’s actors — JaNae Collins, who portrays Reta, and Tatanka Means, the film’s John Wren — to find out how they connected with their characters, how the film resonates today, and what movies shaped them growing up.

First, some backstory. JaNae Collins you might also recognize from Reservation Dogs and Longmire. A Dakota/Crow actress enrolled in the Fort Peck reservation in Montana, JaNae grew up the daughter of a Dakota/Lakota clinical psychologist and a prolific stuntman.

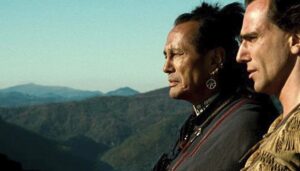

Tatanka Means is not just an actor but a touring stand-up comedian and the son of a legend you might recognize (more on that below). A descendant of Oglala Lakota, Omaha, Yankton Dakota, and Diné, he’s also appeared in Maze Runner: The Scorch Trials, The Son, Reservation Dogs, I Know This Much is True, and several other films and series.

Felipe Patterson to JaNae: Let’s start with Reta. She’s oldest of Mollie (Lily Gladstone)’s sisters and the quiet one. What resonated with you the most about Reta?

JaNae Collins: Her intelligence was particularly noteworthy during a period that feels distinctly different, given it was nearly a century ago. Gathering information about her proved to be quite challenging, and the technical details were elusive. Fortunately, (Executive Producer) Marianne Bauer played a crucial role in aiding my understanding of the character. The historical context was essential, especially regarding the Osages’ guardianship system, which often led to labeling individuals as incompetent. Remarkably, [Reta] stood on the cusp of being deemed competent and capable of managing her own finances.

Felipe: What stood out the most when you first read the script?

JaNae: One aspect that immediately caught my attention was the initial description of her as “the sensible one.” I interpreted this quite literally, especially during the moments in the movie where my character, alongside my husband, undertakes an independent investigation. The divergence in our motivations becomes apparent, with my drive rooted in pure love and anger at the injustices suffered by my family. While her sensibility and competence were initially striking, it was the profound emotions of love and anger that propelled both me and my character forward in the investigation — before the involvement of the FBI in the manner it eventually took.

Felipe Patterson to Tatanka Means: What about Agent John Wren — what was most compelling to you about his story?

Tatanka: He was a Native person within the Bureau of Investigation [the precursor to the FBI] early on. It was quite remarkable to have someone in that position, and it struck me as truly exceptional.

I hesitate to label him simply as a “good guy,” but he was committed to resolving the murders, dedicated to uncovering the truth, and genuinely served a noble purpose. That aspect resonated with me, making it a compelling choice. When I first read the book, navigating through numerous characters and roles, this particular character stood out to me. I immediately felt a connection with this character and knew that he was the role I wanted to portray.

Felipe: Tatanka, did you find any personal connect to Wren?

Tatanka: It’s not so much a personal connection as it is an admiration for his fearlessness in putting himself out there. For a Native person to be involved in law enforcement during that era was a significant departure from the norm. His representation during the birth of the FBI, the Bureau of Investigation at that time, was groundbreaking and monumental.

JaNae: There are parallels between Tatanka and John Wren. Tatanka, is very well-loved in Indian country – everyone admires Tatanka. His comedy, you know, really connects with people, and Tatanka is friendly, real, and genuine. I observed those qualities in John Wren; he skillfully navigated within the community, employing similar methods.

Felipe: Were there any specific scenes or moments that challenged you the most, emotionally or technically, while bringing these characters to life?

JaNae: There was this one particular issue that really preoccupied my thoughts. I asked numerous people in the community why my character married Bill Smith after my sister passed away. It became a point of contention, raising questions about whether it was his fault — or perhaps connected to Ernest’s family. The mystery lingered, and receiving varied responses forced me to form my own conclusion.

How I found peace with it was realizing that, during that time, there were various devils preying on the Wajahjis. For my family, Bill Smith was the devil they knew. It was a case of “the devil you know is better than the devil you don’t.” In that context, he represented a familiar evil, and perhaps, in her perspective, my character didn’t view him as inherently evil. Maybe she saw him as a means to an end, working through him to accomplish tasks because, during that era, native women were often unheard. Even with wealth, they faced a predatory environment, and women’s voices were typically channeled through men. I reconciled it by likening it to the unfortunate reality of the time.

That’s how I moved past it because I was hung up on that aspect for quite some time.

Tatanka: For me it was just being in the courtroom when Leo (DiCaprio)’s character, Ernest, is denying these things. We know that these lies were happening, or he’s changing his story. I found it difficult to watch. Later in the movie, when the FBI was gathering, and John Wren was reporting on what was happening, it became even more evident that there was no justice being served. When we were shooting that scene, I felt a heavy weight, grappling with the frustration of what they were going through at that time.

Felipe: What were some things you learned from working with Scorsese and this talented cast?

JaNae: Wow. Observing Leo and Robert (DeNiro) at work was truly amazing. Watching Marty (Martin Scorsese) and Robert collaborate was equally intriguing; they seemed to share their own unique language. A simple look between them conveyed so much, and you could sense the communication even without words. In contrast, Leo is more introspective, expressing himself through conversation.

Entering the project without knowing Leo personally, I had heard various anecdotes, like being advised not to talk to him out of character. Some of these stories might have been hearsay from people who hadn’t even interacted with him. I felt nervous, especially during scenes where there was a distinct “us versus them” dynamic, particularly between our characters. Leo and Bill Smith had a consistent clash of energies.

I was initially anxious around Leo, considering the tension in our scenes. My character didn’t like him, and I wondered if he might feel the same about me. The uncertainty about whether he employed method acting added to my nerves. It took some time to overcome those concerns, but eventually, I realized it was a valuable experience. Leo and Lily taught me a lot just by observing them work. It was like attending a masterclass.

Tatanka: Yeah, just being on set, surrounded by everyone, and having the opportunity to watch them work, showcasing their skills, was truly unbelievable. Being in the room during the courtroom scene with John Lithgow, Brendan Fraser, Robert De Niro, and Leonardo on the stand, with Scorsese directing and sitting next to Jesse Plemons – it felt surreal. I kept asking myself if I was really there, witnessing this incredible ensemble. I couldn’t believe I was a part of it.

Being able to observe everyone in action was an amazing experience. I felt immensely grateful just to be there, soaking it all in and watching them do their thing.

Felipe: The film can be heavy and just emotional at times. What did you do to decompress?

JaNae: Directly after our scenes, there was a specific moment when Lily (Gladstone) and I were portraying intense grief over the passing of a close relative. It was a particularly heavy scene, with both of us fully immersed, engaging in profound expressions of sorrow – genuine, whale-like crying as if we were truly losing our [relative] in that very moment. However, as soon as we heard the director call “cut,” we swiftly transitioned back to our normal selves.

We often found ourselves teasing Jason (Isbell), most of the time, and Tantoo (Cardinal) would emerge again. She didn’t linger in that reserved and somber state; instead, she revealed her humorous side and engaged in playful banter. During one instance, she focused on Jason, poking fun at his contortion act, where he leaned back dramatically, attempting to convey mourning. She playfully expressed disbelief, injecting humor into the otherwise intense atmosphere.

This humorous interlude had Lily and me cracking up between takes. Marty took note of this, expressing his curiosity about how we could seamlessly shift between laughter and tears. As Native individuals, we have a tendency to turn challenging moments into humorous ones, grandstanding off the humor and escalating it until everyone is laughing. This approach significantly helped ease the tension and grief on set. I firmly believe that humor played a crucial role in bringing us together and providing relief during emotionally charged scenes.

Tatanka: Yeah, it was a very heavy experience. After getting out of the wardrobe and shedding those emotionally charged scenes, especially during the challenging times of COVID, many of us were driving ourselves home. I had my own car, and the journey often took about 45 minutes, sometimes even an hour. During the drive, I would roll down the window, taking in the fresh air, and although I don’t smoke, in our traditional ways, we use tobacco for certain rituals. It was a moment to bless off, incorporating elements from our own tribes and cultures, allowing us to leave the weight of the scenes behind and move forward in a positive way.

The community was incredibly supportive, always present. As JaNae mentioned, laughter is good medicine, and the community provided that healing balm. The invitations from various community members to participate in different forms of ceremony were frequent. Engaging in these ceremonies was a way to renew and bless ourselves, ensuring we were on the right path and encouraging us to continue moving forward. It was a significant source of help and a relieving experience during those intense times.

Felipe: How has working on Killers of the Flower Moon impacted your own understanding of this chapter of history and its relevance to contemporary issues?

JaNae: That’s a good question, and I have a story about that. Looking back on the time period we had to go back into, there was a moment with Lily, Cara (Jade Myers), and Jillian (Dion), where we often spent time together, grabbing pizza at a local spot in Pawhuska (Oklahoma). On one occasion, we joined Margo, who portrayed our older sister in the film and went to a particular saloon in Pawhuska.

Entering that environment was a visceral experience. The majority of the patrons were Caucasian, and as the five of us walked in, it was as if time stood still. The eerie stares we received sent shivers down my spine. It was a moment of realization – a glimpse into the discomfort our characters must have felt. I turned to Lily and remarked that this was likely how they experienced it. We were essentially living what they went through, the feeling of being unwelcome, of being scrutinized.

This memory remains vivid because it wasn’t just a historical recreation; it was a contemporary experience that happened just two and a half years ago. Stepping back into that atmosphere felt like a journey through history, encountering that predatory gaze and the sense of not belonging. It echoed the struggles Native individuals faced in the past, with motives often hidden under a thin veil of exploitation – be it for money, marriage, or other sinister purposes. Experiencing this in a modern context was a profound reminder of the enduring impact of history on our present experiences.

Tatanka: Being able to share this story with our fellow country people who might not have been aware of these historical injustices that were swept under the rug — it is truly impactful. Shedding light on the atrocities that happened to American Indian people during that time is crucial, as there was a glaring absence of justice. Unfortunately, the relevance of this issue persists today, manifesting in various challenges related to state, tribal, and federal dynamics. The red tape still poses obstacles in seeking help and sharing our stories with the government.

The narrative of the film serves as a poignant reminder of the ongoing struggles, mirroring issues like the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and People crisis. The film draws attention to the fact that even during that era, both men and women were going missing, with their murders remaining unsolved, a harsh reality that continues to this day in different places. By bringing these stories to the forefront through entertainment and the collaboration of talented individuals — who have lent their stardom to tell this tale — there’s an opportunity to raise awareness.

I hope that the impact of this story goes beyond its historical context and encourages more narratives to come to light. It’s essential for people to be aware that these issues aren’t confined to the past; they persist, demanding our attention and collective efforts for change.

Felipe: What movies had the biggest impact on you growing up?

JaNae: In my household, Native films held a special place, particularly ones like Smoke Signals, Dances with Wolves, Dance Me Outside, and Skins. We gravitated toward Native cinema and enjoyed a lot of comedic content. Dances with Wolves, in particular, was a film we often referred to, even making jokes about it.

It left a lasting impact on me, and it was one of the first times I saw my movie mother, Tantoo Cardinal, in action. Witnessing her tremendous force and power on film and television was truly remarkable – she’s a powerhouse. Working with her was an absolute joy, and I’m grateful for the experience. She’s everything.

Tatanka: I enjoy the classics like Terminator, the Rocky series, and cowboy movies like Eight Seconds and Urban Cowboy. Among my favorites are, of course, the native films that JaNae has already mentioned, and the impactful Last of the Mohicans, which holds a special place for me as my dad was part of the cast.

At the age of seven, I had the incredible opportunity to visit the set for a month during filming. This experience significantly shaped my perspective, as it was the first time I saw someone I knew in a movie. It made the cinematic world feel more real, breaking the notion that these characters are not tangible. My older brother even had a single line in that movie, a memory etched in my mind.Every time I see indigenous people represented in films, it reinforces the possibility for us to pursue similar paths.

Witnessing the achievements of our best friend, Lily Gladstone, who was nominated for an Academy Award and won a Golden Globe, makes the dream even more tangible for us. It’s a reminder that such accomplishments are within reach for Native kids everywhere – a powerful and inspiring possibility.

Start a watercooler conversation: